The Islay Wave Power Generator

The world's first commercial wave power station is going into action in Scotland.

The power station, on the island of Islay, is the product of years of research into how to effectively harvest energy from the world's oceans.

The UK was one of the world's leaders in developing wave power until a series of setbacks coupled with a lack of funding scuppered promising projects following initial enthusiasm in the late 1970s.

The Islay wave power generator was designed and built by Wavegen and researchers from Queen's University in Belfast and has financial backing from the European Union.

Known as Limpet 500 (Land Installed Marine Powered Energy Transformer), it will feed 500 kilowatts of electricity into the island's grid.

Limpet was born out of a 10-year research project on the island where the team had built a demonstration plant capable of generating 75 Kilowatts of electricity.

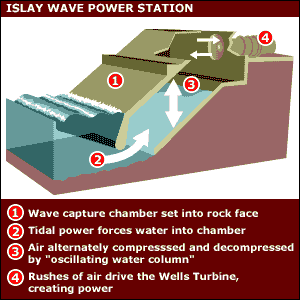

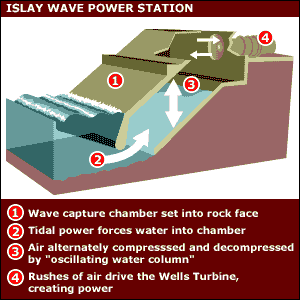

The power generator consists of two basic elements:

A wave energy collector

A generator to turn this into electricity

The energy collector comprises a sloping reinforced shell built into the rock face on the shoreline with an inlet big enough to allow seawater to freely enter and leave a central chamber.

As waves enter the shell chamber, the level of water rises, compressing the air in the top of the chamber.

This air is then forced through a "blowhole" and into the "Wells Turbine", designed by Professor Alan Wells of Queen's University.

The turbine has been designed to continue turning the same way irrespective of the direction of the airflow.

B1b3_d1.1

As

the water inside the chamber recedes as the waves outside draw back,

the air is sucked back under pressure into the chamber, keeping the

turbine moving.

This constant stream of air in both directions, created by the oscillating water column, produces enough movement in the turbine to drive a generator which converts the energy into electricity.

But is it viable?

Wavegen says that there could be sufficient recoverable wave power around the UK to generate enough power to exceed domestic electricity demands.

Furthermore,

renewable energy supporters say some research suggests that less

than 0.1% of the renewable energy within the world's oceans could

supply more than five times the global demand for energy -

if it could be economically harvested.

Furthermore,

renewable energy supporters say some research suggests that less

than 0.1% of the renewable energy within the world's oceans could

supply more than five times the global demand for energy -

if it could be economically harvested.

That would probably involve large-scale wave plants in near-shore or off-shore environments, a technology still being developed.

However, large-scale on-shore wave power generating stations could face similar problems to those encountered by some windfarm projects, where opposition has focused on the aesthetic and noise impact of the machinery on the environment.

Wave power supporters say that the answer lies not in huge plants but in a combination of on-shore generation and near-shore generation (using a different technology) focused on meeting local or regional needs.

On-shore or near-shore plants, they argue, could also be designed as part of harbour walls or water-breaks, performing a dual role for a community.

B1b3_d1.2